Trout aren’t really that fussy, and certainly aren’t suspicious. Put a reasonable impression of food in front of trout and, if they are feeding, they’ll usually eat it.

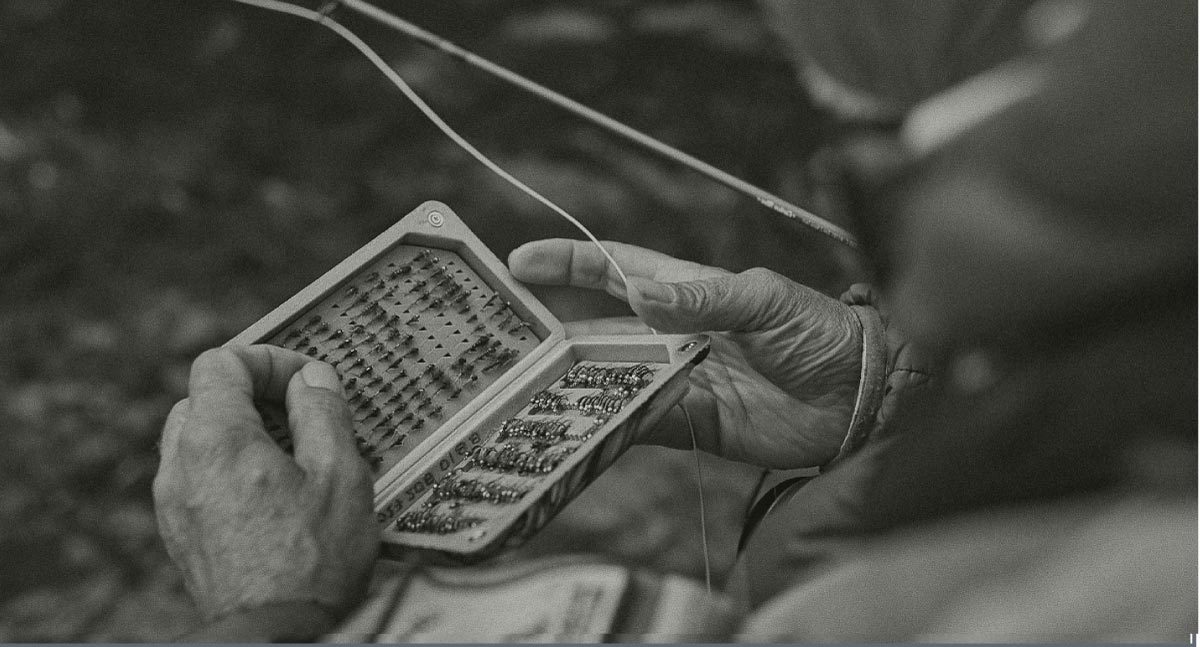

My own fly box is a pretty simple affair these days. The many flies I used to carry have been reduced to a handful of basic designs in a few colours and sizes. Even the colours are limited - mostly buggy greys, olives and browns. For me, a few very simple designs cover literally any situation I come across in trout fishing. There may be a better specific pattern for a particular situation, but so far I haven’t come across a situation where my flies didn’t work at least as well as any other ‘hot’ pattern for the water in question, and often much better. I find this kind of thing encouraging, but it’s not surprising, really.

In the twenty-five years since my book Trout Hunting was written, I’ve had some interesting discussions about one of the central planks in my “theory” of trout fly design. Many of these conversations have involved my fishing pals. The great thing about these discussions is that they take place over weeks and months. We argue away on some incredibly arcane point, then go away and mull it over for a while. Ideas get thrashed out pretty thoroughly. Not so much how to catch them, maybe, but why we catch them with our fly rod.

Several years back I started thinking about something that all predators do when hunting. When they begin to look for food they form what biologists call a ‘search image’. We know that all wild animals have to be efficient in their search for food. They can’t waste energy charging around just trying out anything on the chance it might be food.

Many or most of the critters that predators eat are what the scientists call cryptic, which means they are hard to see. Some blend into the environment so successfully that they aren’t seen until they move. Others have camouflage patterns and visually confusing stripes and spots to make them difficult to separate from a herd or flock. Some prey is encountered in bewildering numbers, relying on the difficulty and reduced probability of being singled out as food. These are what the scientists call strategies, but bugs are obviously not thinking this out for themselves, its innate.

So, the theory goes, the predator narrows its search for certain features that signal food or prey, and this is interesting for us fly fishers. It’s called ‘”imited attention” by animal behaviourists. All predators do this, and what it means is a kind of tunnel vision. The predator, in our case a trout, sort of tunes-in to the specific characteristics of the bug or minnow it is searching for and tunes out almost everything else. The predator responds to the ‘fit’ between its search image and the outstanding characteristics of the prey.

How what we call “selectivity” develops is each time the trout has a successful encounter with a type of food, it reinforces the stimulus. When there is a lot of a certain bug on the water, the trout will narrow its search to that type. This is the most difficult of all the situations fly fishers face. It makes it important to present your fly in a way that fits the trout’s current search image.

This is good news and bad news for the trout. The good news is that by concentrating its attention on that limited bit of visual information, it can feed very efficiently. It doesn’t waste any time or energy on non-food items. The bad news for the trout is that by tuning out most of the other information from its environment, it becomes vulnerable to other predators, like us. Another negative effect is that the trout misses some easy meals of perfectly good food items that it doesn’t recognise. The trout feeds most efficiently when there is only one type of prey in large numbers.

Studies have shown that the detection rate for any single type of prey drops significantly when there are several types available. That means that the trout has to eat the same kind of thing repeatedly to form a search image, and that the search image deteriorates or fades when there are several different types of food around. So, the “selective trout” really doesn’t exist where there is a varied and inconsistent supply of food, which, when you think about it, is most of the time.

A big part of fly fishing’s lore is concerned with just what makes a good trout fly, and we have plenty of them, proven over the years by trial and error. Although scientists have been dealing with the search image idea for decades, anglers have usually done things empirically. There have been lots of theories of course, but the way of a trout with a fly has been regarded as somewhat of a black box mystery. Otherwise we wouldn’t have so many fly patterns. And dreaming up new fly patterns is half the fun, right?

What we are dealing with here, I call “prey Image”. It’s not a scientific term, it just sounds like one. I made it up to describe the image an artificial fly presents to a fish. Naturalistic close-copy flies are an attempt to make the artificial resemble exactly the appearance of the real thing – so that’s clear enough. It makes sense too, but the problem is that close copy flies don’t catch any more fish than the scruffiest and vague impressions. The Woolly Bugger is a good example. So, what gives?

It doesn’t make sense, right? If a fly is an exact copy of the natural, it stands to reason it should work almost as well as the natural. Gary LaFontaine reckoned it was a matter of exaggerated “triggers”. Good flies have, he said, salient features that trigger a feeding response in the trout. Scientists call this trigger thing a ‘behavioural releaser’. It’s part of an explanation for animal behaviour that includes genetically determined responses to certain stimuli. Like the partridge dragging a wing to lead a predator away from the nest. All partridges do it instinctively, and all the partridge’s predators respond to it instinctively. What LaFontaine was suggesting is that certain exaggerated features in a fly act as a trigger to this kind of instinctive response.

I like the search image and trigger idea and believe it describes what’s going on in a trout’s brain. But there’s some flexibility there that needs explaining. And I still don’t know for sure why a vague, scruffy impression of a bug should work better than a close copy replica of the trout’s real food. But I have another theory bubbling away.

GISS is a twitchers (birder watchers) acronym for General Impression Shape and Size. Birders use this for identifying birds they see in the wild. They even have a book on it, with impressionistic silhouette images of birds, rather than the detailed textbook images we are all used to seeing in bird books. These silhouette images are apparently more useful for spotting birds than the detailed profiles.

It makes you wonder if something like this is what’s going on with trout flies. I think the simple buggy and fishy patterns present a strong, generalised ‘prey image’ rather than an ‘accurate’ simulation. It may be, and to my mind probably is the case, that the trout’s search image is geared more to the general impression, shape and size than it is to any particular detail.

I treat the generalised design as the basis for my whole approach. I might tweak a particular model a little, maybe add something like rubber legs for more life and ‘kick’, or I might add some touch of colour or flash for certain conditions, but they stay pretty much the same from year to year. Usually I just use the bog standard versions in those dowdy bug colours, and adjust for size. They always work and I know I can go anywhere that trout swim and not feel handicapped by my fly collection.

This approach has been met with scepticism by several anglers and guides in several countries, but it hasn’t failed me yet. When I go to the Kootenays in B.C. for instance, I take the same flies I take to New Zealand, or to northern Scotland. I’ll add a few local variations – like big ones with rubber legs for the western Golden Stonefly hatch, or a dark claret seal’s fur body for the northern Scottish lochs.

The thing is, if you only have a couple of flies in a range of sizes, you waste no time searching for “what the trout want” in a hatch situation. Get the size in the ballpark and get down to the business of catching fish. The reason, of course, is that trout aren’t really that fussy, and certainly aren’t suspicious. What’s really going on is that they’d rather eat something than go hungry. Put a reasonable impression of food in front of trout and, if they are feeding, they’ll usually eat it. My pal Carl McNeil in New Zealand calls it the “urinal cake theory” of fly design.

Carl says, if you put a urinal cake in a bowl of marshmallows and offered it to a kid, the kid would try to eat the urinal cake, especially if he’s eaten a marshmallow before. He’s at least going to take a bite out of it, right? Why wouldn’t he? He has no reason to suspect there’s a urinal cake among the marshmallows. The urinal cake presents the prey image of a real marshmallow, more or less - the general impression, shape and size. (Needless to say, don’t try the urinal cake experiment at home with real kids. This is what scientists call a “mind experiment”.) The point is, what possible reason would there be for a trout not to eat something that looked more or less like a bug it usually eats? As long as the fly behaves naturally enough, there is no reason for a trout to “suspect” anything.

These generalised flies form the base of my entire battery. I’ll use them anywhere with complete confidence – maybe the most important thing in the whole game. You can build your own base using whatever general fly designs and patterns you want. There are some good ones to choose from out there, some more complicated than mine and maybe more fun to tie. But, once you start thinking about trout flies using the GISS idea, and how trout probably really behave, you won’t go back to worrying about whether the hackle on your Parachute Adams is the right shade of grizzly.

You can shop Bob Wyatt's most celebrated trout flies here.

|

Words by Bob Wyatt

Canadian born, now residing in Scotland, Bob has been a fly fisherman since 1956, and a fly tier since the age of thirteen.

Having cut his angling teeth on the classic freestone rivers of Alberta and British Columbia. His writing on fly fishing and related topics has appeared in esteemed publications across the world. |